Degree-level apprenticeships - Enabling framework

Introduction

This enabling framework is designed for key system stakeholders involved in the development and delivery of Degree-Level Apprenticeships(DLAs), including employers, industry and professional bodies, tertiary education organisations (TEOs), Industry Skills Boards (ISBs) and government.

It is designed to assist these key system players to align their roles, responsibilities, and investments to support high-quality, work-integrated degree programmes that are accessible, sustainable, and fit for the future of learning and work in New Zealand.

Purpose

The purpose of this enabling framework is to:

Identify and articulate the key conditions and system settings required to support the sustainable delivery of DLAs in New Zealand.

Provide a structured basis for policy development, regulatory adjustments, funding decisions, and sector readiness initiatives, informed by local and international experience.

Support the design and implementation of pilots and demonstration models that test new approaches to co-delivery, assessment, learner support, and quality assurance.

Facilitate collaboration and alignment between key actors, including tertiary education providers, employers, ISBs, government agencies, learners, and iwi/Māori partners.

Lay the groundwork for a long-term systems shift, enabling DLAs to become a recognised, valued, and accessible pathway to higher education and skilled employment.

This framework is intended to guide both short-term action and longer-term systems change. It builds on design discussions already held with stakeholders across the education and industry sectors and reflects principles of equity, flexibility, and partnership at its core.

What is an Enabling Framework?

An enabling framework sets out the essential conditions, structures, and supports needed to make a new model like degree-level apprenticeships work in practice.

It doesn’t prescribe a single solution but identifies the policy, funding, regulatory, and operational enablers that must be in place for successful design, delivery, and scale.

Context

New Zealand’s tertiary education and training system is under pressure. Employers across sectors have raised concerns about the relevance and responsiveness of formal qualifications, with some increasingly investing in offshore, in-house, or informal training models[i]. At the same time, provider funding is constrained despite rising delivery costs, learner achievement remains uneven[ii], and the promise of lifelong learning is not yet a reality for many[iii].

Yet New Zealand also has strong foundations. Our universities are internationally respected, and we have a long history of delivering education in the workplace. Many employers are familiar with training processes and invest significantly in staff development. Workplace-based learning has demonstrated strong post-study employment outcomes[iv].

A substantial portion of degree-level education in New Zealand is vocational in nature with up to 82% of degree programmes at universities alone are estimated to have an applied or work-oriented focus. Work-integrated learning is already a key feature of many degrees, including internships, industry projects, and simulated workplace environments.

There have been several attempts to pilot DLAs most notably in engineering, initial teacher education, and recently in the construction and infrastructure sectors. However, the pace and scale of uptake in New Zealand contrasts sharply with the more coordinated and accelerated implementation observed in countries such as the United Kingdom, Germany, France and the United States of America[ix].

The tertiary system is once again undergoing change, with government signaling a stronger focus on work-based provision across polytechnics, wānanga, and private training establishments.

Taken together, these conditions suggest New Zealand is well-positioned for a step-change in the uptake of DLAs. This enabling framework outlines the current enablers already in place, and identifies the policy, regulatory, and funding adjustments both incremental and structural that could accelerate the adoption of this model nationwide.

Systems change

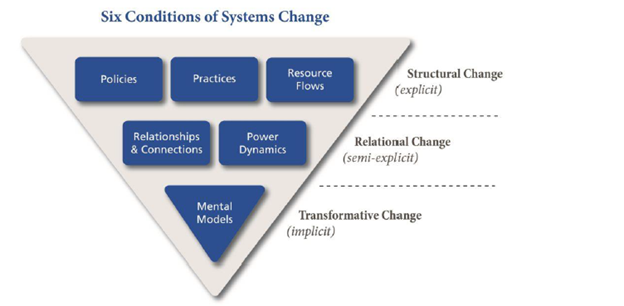

This enabling framework is organised around the six conditions of systems change.

The key advantage of this model is that it helps us tackle problems by changing the underlying conditions that keep them in place, especially those that create or reinforce inequity.

True systems change means being open to changing not just the system, but also how we think and act within it. For funders and policy-makers, this means recognising that their own assumptions and behaviours may need to shift too.

The model also shows that lasting change happens at three levels:

Structural change (like policies, practices, and how resources are distributed),

Relational change (how people relate to one another and how power is shared), and

Transformative change (shifting mindsets, beliefs, and assumptions).

These levels are shown in the reverse triangle (see image).

Policies

Policies in this context relate to formal rules, priorities, and strategies set by government and its agencies that shape how tertiary education is delivered and funded.

They influence what programmes are possible, which learners are prioritised, and how institutions and employers are incentivised to participate in new models like degree-level apprenticeships..

Current state:

No dedicated policy framework exists for degree-level apprenticeships.

Work-based learning is primarily recognised as a sub-degree option.

DLAs are not formally recognised in legislation or TEC Investment Guidance.

There is no systematic support or requirement to develop and implement DLAs.

Research is the default focus of academic staff teaching on degree-level programmes.

Quick wins:

TEC Investment Guidance explicitly references DLAs as a priority.

Tailored guidance from TEC and NZQA clarifying how DLAs can meet existing quality assurance and funding requirements.

Bolder steps:

The Education and Training Act defines degree-level apprenticeships as a distinct category of work-based provision and makes research requirements for advanced programmes more flexible.

National policy framework that outlines principles, expectations, and minimum standards for degree-level apprenticeships.

ISBs (from 2026) incorporate degree-level apprenticeships into ‘industry-endorsed networks of provision’.

Student visa holders can work up to 37.5 hours per week when enrolled in a degree-level apprenticeship.

Professional regulatory bodies recognise degree-level apprenticeships as valid pathways to professional registration. n.

Practices

Practices refer to the everyday actions, processes, and habits of organisations and individuals that shape how education and training are delivered. These include teaching and learning methods, industry engagement approaches, learner support systems, assessment design, and how programmes are developed and managed.

Practices influence whether degree-level apprenticeships are implemented with fidelity, quality, and learner success in mind.

Current state:

Most degree programmes place the provider-led, campus-based model at the centre.

Work-integrated learning is typically a component, not embedded throughout.

Industry tends to be consulted, rather than co-designing and co-delivering learning.

Assessment often privileges academic outputs over authentic, workplace-based evidence of competence.

Limited guidance exists on how to blend academic and employment roles.

Quick wins:

Practice guides, templates, and exemplars for DLA programme design, co-assessment, and employer-educator collaboration.

Professional development for academic staff, training advisors, and employer mentors to support DLA delivery.

Dual-admissions models that align employer recruitment processes with academic entry requirements.

Joint curriculum development workshops that bring TEOs, industry, and professional bodies together to co-design DLA pathways.

Bolder steps:

Programme approval and accreditation processes to explicitly recognise co-designed, co-delivered degree-level apprenticeship models.

National community of practice for degree-level apprenticeships implementation, to support peer learning and innovation in delivery practice.

Different performance measures.

Resource flows

Resource flows refer to how funding, staffing, infrastructure, and information are allocated and distributed across the system.

These flows determine which types of education are financially viable, which organisations are incentivised to participate, and whether learners and employers can access the support they need.

Current state:

The funding system does not support or differentiate DLAs from other degree provision.

There is no formal mechanisms for co-investment between TEOs and employers.

TEC funding privileges provider-led delivery and campus-based models.

Learners bear the costs of professional placements

There are no distinct tracking of DLAs.

Quick wins:

Costing model for degree-level apprenticeships that reflects shared delivery, dual support roles, and flexible learning modes.

Default TEC funding approval for new degree-level apprenticeship programmes.

Employers who offer degree-level apprenticeships can access Apprenticeship Boost.

Bolder steps:

Dedicated tax credits or a levy-offset mechanism to support employer participation in degree-level apprenticeships.

Reprioritised and ring-fenced DQ 7+ funding to support the development of qualifications and programmes for degree-level apprenticeships.

Base funding for new degree-level apprenticeship programmes is fixed at a minimum of ten full-time enrolments for the first three years.

Use procurement levers (e.g. public infrastructure projects) to require or incentivise degree-level apprenticeships.

ISBs, professional organisations or iwi organisations are able to purchase degree-level apprenticeship programmes directly.

Relationships & Connections

Relationships and connections refer to the networks, trust, and collaborative behaviours between stakeholders in the system, including learners, employers, educators, iwi/Māori partners, professional bodies, and government agencies.

Strong relationships enable shared ownership, smooth transitions, and mutual accountability across the learner journey. Weak or siloed relationships are a major barrier to successful DLA implementation.

Current state:

Relationships between TEOs, employers and professional organisations vary significantly by sector and region with some that are strong and long-standing, others are transactional or non-existent.

Co-design of programmes and shared governance is not common practice in most degree-level education.

Learners often act as the bridge between disconnected systems, without coordinated support from both employer and provider.

Engagement with iwi, Māori industry leaders, and regional stakeholders is uneven and often not embedded in governance structures.

Quick wins:

Partnership agreements (e.g. Memoranda of Understanding) between TEOs and industry for degree-level apprenticeships pilots that outline shared roles and responsibilities.

Map existing networks and leverage established partnerships to seed degree-level apprenticeship opportunities.

Dual-support models where both an academic advisor and a workplace mentor work with each learner.

Group employer schemes expanded to include degree-level apprentices. .

Bolder steps:

Co-governance requirements into degree-level apprenticeships design, delivery, and evaluation, including shared curriculum oversight and decision-making structures.

Regional or sectoral “degree-level apprenticeships Hubs” coordinate stakeholders, broker relationships, and share resources.

Power Dynamics

Power dynamics refer to how decision-making authority, influence, and accountability are distributed across the system. In traditional tertiary education, power often rests with education providers and regulators.

For DLAs to succeed, power must be more equitably shared with employers, learners, community partners, and industry, particularly in the design, delivery, and governance of programmes.

Current state:

TEOs lead degree-level education with employers positioned as optional contributors.

Employers have limited influence over curriculum design, assessment standards, or learner selection in most degree-level qualifications.

Māori lack tino rangatiratanga over most degree-level education.

Government controls funding, regulation, and policy settings, with little devolution.

Quick wins:

Shared decision-making structures for all degree-level apprenticeship programmes.

Extend the use of Māori-led frameworks for degree-level apprenticeships.

Redesign funding approval processes to require co-designed proposals with industry or professional groups.

Bolder steps:

Establish governance mechanisms at the national level to steer the strategy and oversight of degree-level apprenticeships.

Provide targeted support to employers and other partners to lead or co-lead degree-level apprenticeships development in their sectors.

Mental Models

Mental models are the deeply held beliefs, assumptions, and narratives that shape how people interpret the purpose and value of education.

These include perceptions of what a “real” degree looks like, who higher education is for, and how learning should be delivered.

Shifting mental models is essential to making degree-level apprenticeships (DLAs) a mainstream, valued option rather than a niche or second-best pathway.

Current state:

Degrees are still widely viewed as academic, classroom-based qualifications, with limited recognition of workplace learning as legitimate or equivalent

Apprenticeships are often associated with lower status trades training, not with professional careers.

Many learners, parents, and educators see work and study at degree level as separate or sequential, not as integrated or mutually reinforcing.

Cultural bias persists against applied learning models, particularly within some parts of the university sector and professional bodies.

DLAs are not widely understood or visible in the public narrative about tertiary education and career success.

Quick wins:

Promote real-life stories of successful degree-level apprenticeship learners, employers, and educators through media, events, and social campaigns.

Integrate degree-level apprenticeships into career guidance tools and school outreach activities as credible, aspirational pathways to high-value jobs.

Sector champions advocate for degree-level apprenticeships within their professional networks and institutions.

Run workshops and briefings for governance groups, academic boards, and regulators to build shared understanding of degree-level apprenticeships models.

Bolder steps:

Launch a national communications campaign to reframe perceptions of degree-level apprenticeships as high-status, high-value pathways equivalent to traditional degrees.

Embed work-based learning and apprenticeship principles into professional development for staff involved in degree-level programmes.

Incentivise academic and employer collaboration through recognition, awards, or performance funding tied to degree-level apprenticeships outcomes.

Partner with iwi, Pacific communities, and regional employers to co-create new narratives about learning and earning that reflect diverse aspirations and cultural values..

Conclusion

Degree-level apprenticeships offer a powerful opportunity to rethink how higher education is delivered, accessed, and valued in Aotearoa New Zealand. They bring together the strengths of our education and employment systems combining academic knowledge with practical experience, and creating new pathways to success for learners, employers, and communities alike.

This enabling framework outlines the key system conditions, policy, practices, resource flows, relationships, power dynamics, and mental models, that must be addressed to unlock the full potential of DLAs. It highlights that no single actor can deliver this change alone. Progress depends on shared commitment, coordinated action, and a willingness to test, learn, and adapt together.

By aligning funding, regulation, pedagogy, and partnerships around a shared vision of high-quality, equitable, and employer-integrated learning, we can build a more responsive, inclusive, and future-fit tertiary education system.

The framework is not a blueprint, but a starting point. It invites system leaders, educators, industry partners, and iwi to take bold steps now, while laying the foundations for future change.

Planning

-

Getting ready

Find out if you are ready for degree-level apprenticeships

-

Market need

Understanding if there is a market need or demand for DLAs

-

Admissions

Check if your admissions processes are DLA ready

Guidelines

-

Guide for employers

An introduction to degree-level apprenticeships for employers

-

Guide for apprentices

An introduction to degree-level apprenticeships for learners

-

Guide for TEOs

An introduction to degree-level apprenticeships for tertiary education organisations