Degree apprenticeships in New Zealand: their place in the landscape

An earn-and-learn model is slowly gaining ground, one of many choices for marrying theory and practice.

Deciding whether degree apprenticeships are the right tool for a given profession means situating them in the broader landscape of tertiary education. This paper takes stock: how far has New Zealand gone in adopting degree apprenticeships, and how they sit within the continuum of work-integrated learning (WIL).

Degree apprenticeships marry degree-level study with paid employment. They are the most immersive form of WIL, which Patrick et al. (2008) neatly describe as “an umbrella term for a range of approaches and strategies that intentionally integrate theory with the practice of work within a purposefully designed curriculum”.

Work integrated learning takes many forms

WIL spans a spectrum from short industry projects and clinical placements to full employment-based pathways. Most learning about a job still happens in the workplace; the difference with WIL is that it is structured, assessed and credentialled.

New Zealanders may first encounter WIL in secondary school, where the Gateway and Trades Academy schemes aligned with Vocational Pathways put many of the 26,000 participants into workplaces in 2024.

Participants are more likely to complete upper-secondary qualifications and to move into employment or apprenticeships (Earle, 2025). But they account for less than 10% of secondary school students, and only 5.8% of school-leavers —about 3,700 in 2024 —step straight into apprenticeships or traineeships.

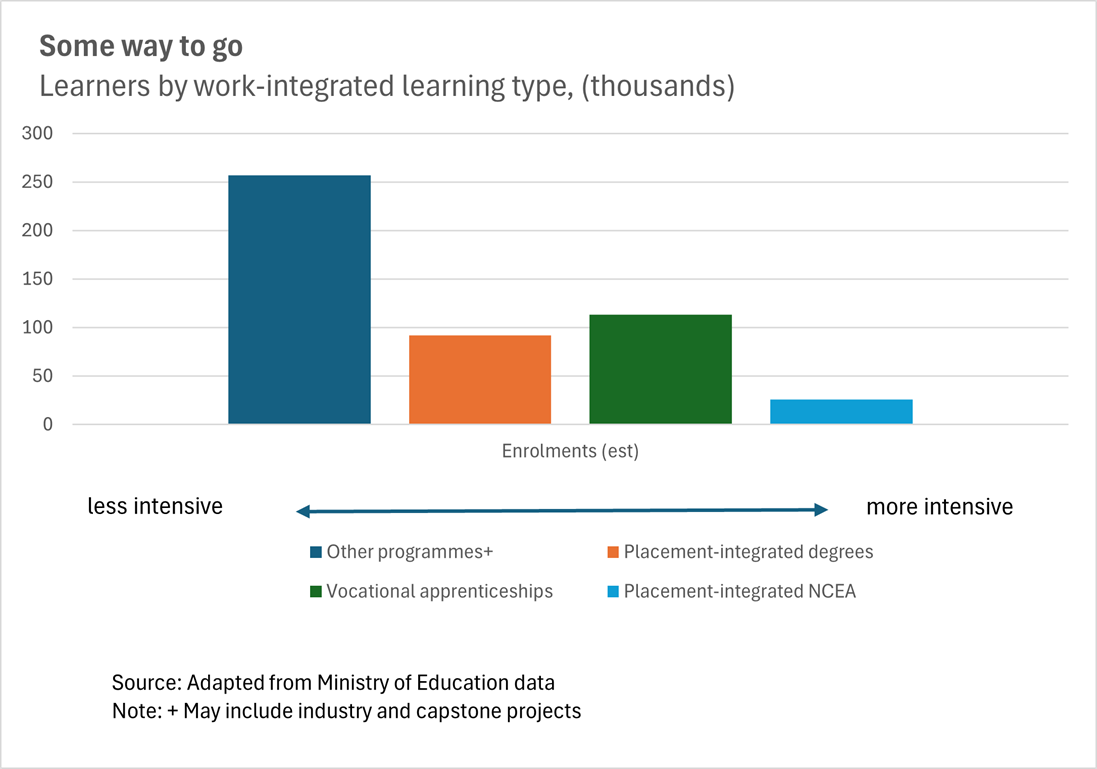

The main options for WIL at a tertiary level are threefold. First, industry traineeships and apprenticeships at levels 3 and 4 on the national framework enrolled around 113,000 people in 2024, mostly via industry training organisations.

Second, 92,000 people enrolled in undergraduate and postgraduate degrees that involve clinical and professional placements, often mandated by professional regulatory authorities.

Third, around 257,000 enrol in other programmes that involve some work-simulated learning, often very extensive for vocational programmes or industry or other capstone projects that usually form only a small slice of the qualification for degrees (adapted from (MoE, 2025).

Other models deliberately step outside the traditional tertiary education pipeline. Chartered Accountants Australia and New Zealand are launching an apprenticeship-style programme in 2026. This programme prepares employees in accounting firms to undertake the Chartered Accounting registration programme without requiring a Bachelor’s degree.

And each takes a different approach to work-integrated learning

The industry traineeships and apprenticeships generally have the most extensive work-integrated learning. The work that these employees do is tightly related to their learning and assessment.

Those enrolled in programmes with clinical and professional placements, in fields such as nursing, teaching and engineering, generally have more extensive work-integrated learning, but only as part of their programmes.

The least intensive but most common type involves programmes that often incorporate industry-linked projects or capstone projects, or involve pre-trades training with extensive work-simulated learning.

The finishing of graduates often still happens in the workplace

Even where degree programmes include structured WIL, much of the “finishing” that turns a graduate into a productive professional happens after graduation. In some fields, this post-degree stage is formal and regulated: medical graduates spend two years as house officers before entering specialist training; new teachers undertake a provisional registration period under a mentor; lawyers complete supervised legal practice.

In others, it is guided by professional standards rather than licensing, as in engineering, where emerging professionals are expected to deepen their competencies before achieving chartered status.

In many workplaces, the process is bespoke: a period of structured induction, mentoring and gradual exposure to more complex tasks, shaped by the organisation’s needs and culture.

This finishing phase can be as decisive for long-term competence as the degree itself, yet it often sits outside the formal education system and is funded, managed and quality-controlled in different ways. We’ll have more to say about that when our research into capstone assessments and how they interface with the requirements of professional registration bodies is released by ConCOVE in the coming weeks.

Degree apprenticeships cut through the clutter

Degree apprenticeships build on New Zealand’s robust WIL base, offering a structured, credentialled route where employment and study reinforce each other. They offer intensive work-integrated learning and bring the ‘finishing’ of graduates forward in their careers are an emerging model in New Zealand.

The existing programmes include BEngTech in Infrastructure Asset Management, the country’s first degree apprenticeship; Teach First NZ, where people work in the classroom while they complete teacher training and a postgraduate diploma; and practice-based Master’s programmes training people for professional roles like Clinical Psychologists or Nurse Practitioners.

New programmes are coming on stream. The Construction and Infrastructure Centre of Vocational Excellence is backing three intakes, with some beginning from 2026: Bachelor of Architectural Technology, Bachelor of Construction Management, and New Zealand Diploma of Quantity Surveying. And Otago Polytechnic is looking to offer a new occupational therapy degree from 2027.

In each, apprentices are employed in the industry while studying, blending learning on the job with academic modules.

How do I get started?

Working out if a degree apprenticeship makes sense for your business, profession, or tertiary education provider isn’t always straightforward. The soon-to-be-published ConCOVE guides for learners, employers, and tertiary education providers will help you navigate important decisions, like whether there is a need and a market for this option, which roles are best performed by employers and which should sit with tertiary education providers, and how each can work together to support apprentices effectively.

A clear eye and candid partnerships can reveal whether a degree apprenticeship is the right tool for the job.